Journal Entry

Week 8

7.21.13 – 7.31.13

This entry is the Istanbul wrap up- closing my journals with thoughts on my research, AKP/Turkish politics, and the city itself.

In terms of my research, I had a really interesting personal moment of analysis while writing my “analysis” section. Dana witnessed it and it was quite funny. She came to my room to ask me a question, and I remember being so excited to talk about what was happening in my brain at that very moment. I realized that no matter how crazy, how eccentric, how defiant, how outlandish, or how much I don’t agree with their tactics at times, I will always root for Turkey. I will share a portion of my analysis section here for context:

Turkish sources agree that while generosity towards its Syrian neighbors is directly related to the philosophy of its new foreign policy, humanitarian action as a new instrument is largely informed by its cultural familiarity with the plight of refugees. In Islam, refugee situations are understood through the migration of Muhammad and his followers from Mecca to Medina. As a result of the experience, the Koran reflects the treatment of refugees and migrants in its teachings by observing the concepts of hijrah (to migrate, to create a new horizon), ansar (helper, receiver of migrants), and muhajir (emigrants, refugees). Halim Yilmaz, Mazlumder’s Director of Refugees, further explains the conception of migration by stating that,

“To migrate is a human and humanitarian condition. In sociological terms we can say that people who migrate from one country or land to another are often more dynamic and efficient to set up new establishments, new regimes, and new kinds of mentalities because they are highly mobile. When we compare this to static societies, and static persons, and static civilizations, we see that throughout history those who are more static tend to fall easier in terms of morality.”

In this light, this research firmly believes that Turkey’s humanitarian actions towards Syrian refugees are being mistakenly judged and evaluated by the international community. Failure to view Turkey through its own lens, and instead, placing it in a Western paradigm fraught with realist security threats and starkly uneven power dynamics, is to deny understanding the additional motivating forces and values that drive the country. This shortsighted scope that Western politics and academics subscribe to for Turkey’s role in the world is precisely the most common and debilitating limitation that the country seeks to defy.

I will always place Turkey as a force that can change the narrative. I actually hope that it does. I think it would do the world good to have a different voice in its recognized powers, especially one that is Muslim. AKP is far from perfect, but I agree with a Turkish friend when he told me that they are human and should be treated as such. Turkey, as a whole, is enjoying options that didn’t exist 20 years ago. As my friend was sharing, the current public response to AKP- deified praise or thousands taking to the street demanding a resignation- lacks the humanity aspect. Despite its faults, much of Turkey’s resurgence in the world is due to AKP. Love them or hate them, it would be difficult to replicate Turkey’s current politics without them. And I am really quite fascinated with Turkey’s politics.

Istanbul today is just as alluring as it was centuries ago. I wonder if that first day when I landed, driving from the airport and seeing the haze fall on the hills and the minarets peek from the top compares to the way men and women felt while taking the Orient Express into the Old City for the first time. There is something about this place, amidst its frustrating logic that takes time to tap into, that captures you. A city, that I could swear for the past two months must be anthropomorphic because of the way she conversed with me every day. Its in the way she punishes and holds out, only to shower your moments with magic immediately after. The way her Bosphorus necklace never dulls and draws your gaze to it once again. Its her sounds letting you know she is still calling for more lovers and conquests- spoons against a cay glass, tires and wooden carts on the cobblestone, the tone of voice of her people, her traditional songs seeping from windows to serenade her to this day. Istanbul is the woman we all love to fight with because making up with her is just too good. We’ll crave her until we are back for more, just like the rest.

CONSIDERING CONSERVATISM

Recently I have been curious about the case for conservatism. The word itself is widely used as a way to characterize political and religious trends of populations, constituting the focused end of the spectrum that stands in direct opposition to its wide-leaning liberal counterparts. For the sake of basic definitions, “conservative” is usually understood as a form of adherence to traditional values, with a tendency for caution in terms of change or innovation. “Liberal” on the other hand is usually considered as being open to new behaviors and views, possessing a willingness to veer from traditions for the sake of possibility.

In a well-known TED talk, Jonathan Haidt presents his Moral Foundations Theory as a way to understand the differences between conservatives and liberals, be it in terms of culture, religion, or politics. For Haidt, the premise that divides conservatives from liberals depends on one’s Openness to Experience, and how it informs decisions on a five-point value system which include: (1) Care for others/Do not harm, (2) Fairness/Justice/Equality, (3) In-Group Loyalty, (4) Respect for Authority, and (5) Purity. His talk explores the tendencies of each group as they would respond to these moral dilemmas, explaining how openness to experience and adherence to traditional values plays a pivotal role in predicting behavioral outcomes. His thoughts are worthwhile, and worth exploring here: http://www.ted.com/talks/jonathan_haidt_on_the_moral_mind.html.

Thinking about the appeal of conservatism is an interesting mental exercise seeing as I consider myself a rather progressive thinker, I think attending The New School counts as standing evidence towards these tendencies of mine. Saying that, I can say that I tend to shy away, and sometimes defensively steer clear, of any type of conservative anything. But then I started thinking to myself- what are its ideological appeals? Why are conservative religious movements on a perpetual rapid rise around the globe? We haven’t all turned into pagan worshipers yet; why? What is it that people find refuge in? I realized that amidst my disinclination for anything of a restricted nature, I had forgotten the meaning that others found in it for themselves. In terms of religious conservatism, people experience deep personal meaning as a result of (hopefully) a spiritual journey. Just because one’s personal quest lands them on the other side of the spectrum as myself, it doesn’t make them any less authentic. (Hold on one second while I repeat that to myself a few times.)

I have decided I would try to understand the appeal of this so I can understand why conservatism continues to hold such a prominent place in just about every type of organizational narrative and continues to attract members around the world at unprecedented rates.

In terms of Turkish politics, one thing that I find particularly interesting is that liberalism was considered the chief enemy of the Republic during its intense period of ideological state and nationalism construction (what we call Kemalism). According to Jenny White in Muslim Nationalism and The New Turks, this fear could be understood as follows;

“If you belong nowhere and your loyalties are not fixed, you have no soy, no recognizable social identity. Consequently, you are suspected of having no honor, a concept that speaks directly to your ability to uphold the standards of your family and community. Liberals, by the very nature of their very willingness to cross boundaries and mix everything from ideas to food in fusion restaurants- not to mention the sexes- fall into this category. “What liberalism did”, Ozel explained, “it gave you combinatorial freedom. I don’t have to like you to work with you because there’s a common benefit. I don’t judge you by your essential characteristics.” But in the Turkish context, liberalism is not respected because it is soysuz, without a tribe. “The greatest enemy of the Republic was liberalism,” Ozel continued. “The greatest sin of Jews was the that they were cosmopolitan.” People were afraid of cosmopolitanism because it was rootless, soysuz. People can change their minds, “sell their own”. Liberals, in other words, have no allegiance, no hard-and-fast boundaries, no political, racial, or ethnic family, and thus, no honor.” (pg 106).

This idea has repeatedly crossed my thoughts while being in Turkey, specifically in terms of the future of the country and myself. One day while riding the bus on the way to Mazlumder, Joel and I were discussing national and ethnic allegiance, and to what extent we identified with this ideas. In terms of nationality and ethnic identification, it was a saddening realization to feel a disconnect with both; on one hand I have an Americanized and diluted version of Mexican, Yaqui, Russian, and Czech ancestry with little cultural attachments to them, and on the other, a sometimes rather problematic relationship with the American nationality that wedged itself in the middle. In that moment, there was sadness rooted in envy for those who upheld the traditions and fostered a deep connection with their culture. My mind’s counterargument was somewhere in a personality trait of wanting to explore while being uncontrolled by such forces.

Now, religiously speaking, the conservative – liberal debate takes on a different form. An often extremely frustrating form at that. When considering conservatism it comes first the recognition that some people prefer to adhere to some sort of moral order. But why? Is it as simple that some people will live accordingly so that they receive their eternal reward at the end? What is it that draws some, but not everyone?

I grew up religiously conservative, and attended a religious college for my undergrad, so I am quite familiar with this type of life. Even from my own experience, there was always a constant source of authority to answer to for my actions. It gave my life a framework from which my choices could be made. (Interestingly enough, since that time, my life itself, has become the framework for which I now make choices. But this is about conservatism, after all.) One thing that I cognitively attach to this period is the absence of control over my mind, due to constantly “surrendering”. Even my mind was subservient to another power. Is this an important way for some people to live their lives? In a constant state of surrender? If you are constantly surrendering, at what point do you lose the fight?

In I am Istanbul, one of the characters asks, “Is it so bad to be governed under Islamic law as laid out by God? Besides, conservatism is on the rise around the globe, not just in Turkey. There’s a growing hunger for spiritual values. Why does this cause so much agitation and alarm here in Turkey?” (p. 137). I wonder, what are the spiritual values that people are hungry for? Are we hungry for order? For reciprocity?

In a book that is no longer available in the New School’s online library, but that I read last semester, titled, Global Salafism: Islam’s New Religious Movement, tracks the rise of this religious sect in the Middle East. Salafi’s are a burgeoning presence, especially in Egypt, and their presence is contested. On one hand, I remember the book forwarding the idea that Salafism was on the rise because of the unattached, free-wielding conditions the globalized world had created. Essentially, humans would always look for some sort of attachment, and as the world order becomes unattached to morality, people, especially in religiously conservative societies, would become attracted to this type of membership. Or as Meijer writes, the appeal of Salafism lies in its transformation of, “the humiliated, the downtrodden, disgruntled young people, the discriminated migrant, or the politically repressed into a chosen sect that immediately gains privileged access to the Truth. Salafis are therefore about to contest the hegemonic power of their opponents: parents, the elite, the state, or dominant cultural and economic values of the global capitalist system as well as the total identification with an alien nation which nation-states in Europe impose. Because its emphasis is on doctrinal purity and not politics, Salafism has been able to empower individuals by providing a universal alternative model of truth and social action.”

On the other hand, Mona Ethaway, a prominent author on women’s rights in the Middle East as well as the revolutionary events in Egypt since 2010, argues that this type of presence is catastrophic to liberal, human rights based ideals, “What hope can there be for women in the new Egyptian parliament, dominated as it is by men stuck in the seventh century? A quarter of those parliamentary seats are now held by Salafis, who believe that mimicking the original ways of the Prophet Mohammed is an appropriate prescription for modern life. And we’re in the middle of a revolution in Egypt! ”

In the case of Mona Ethaway, a fearless intellectual American-Egyptian writer who suffered sexual assault on the streets surround Tahrir Square in 2010, I wonder: Is there a gender dynamic to conservatism? Or maybe, is it globalism that is pushing people closer together in religious conservatism? This can be seen in politics and religion as two separate areas. Politically, it could be argues that in the face of foreign interdependence and the quest for regional authority, AKP espouses an interior narrative of conservatism. During an interview with Abdurrahman Babacan from Mazlumder, the increasing regulations were not problematic; in fact, they were to way to rein in the future wayward morality of Turkish society. In fact, working with Babacan this summer revealed that the morality of future generations is one of the motivating factors behind the different AKP imposed restrictions.

Is this a response to declining of nationalism that people will find belonging elsewhere? A sense of community? Of solidarity? Of a greater meaning as a part of a larger story? It is worth noting that the rise of political Islamism has come on the heels of globalization. The correlation of this trend is worth exploring through future research, but until then, should not be ignored. Considering Western fears are deeply rooted in concern over Islam, it would in our best interest to learn what may be breeding radicalization of an age-old religion like Islam. If the conditions that cause our fear are a response to the conditions that the West creates, the finger is pointing right back at us all along. I believe that we should not proceed through life in fear, but rather with understanding. Okay, obviously I know- if only it were that easy. For me, trying to understand conservatism was not an ideal endeavor- but I found some sort of common ground in doing so. I may not be religiously conservative, but I enjoy hearing and learning about spiritual (and cosmic) journeys of people. A conservative’s may not be as far out, but it sure as hell is just as important, to them.

Journal Entry

Week 6

7.7.13 – 7.13.13

Interning at Mazlumder has been an exceptional experience. The beginning was marked by a period of being “shockingly unshocked”, that is to say the initial impact I was expecting from the organization was actually much smoother than anticipated. I don’t mean that in a sense that Mazlumder does not do and say things that are aligned with a completely different orientation than I am used to; they most certainly do. It’s just that the introductory stage of working here was without major struggle or tension, where instead I have felt like a sponge that isn’t there to grant a critical lens on their activities and mission, but to first and foremost soak it in and learn from it. I think that many people would find this problematic, because after all, shouldn’t it challenge some of my previous held conceptions about life? Shouldn’t I wrestle with things? Absolutely. And of course I do. But I have thought more about what they have to teach me about how to view the world, rather than how it challenges my own convictions on how the world is ordered. In this journal, I am going to cover three aspects of working with Mazlumder: First, I will cover a brief introduction to the history and activities of the organization. Next, I will discuss three major concepts that have been reintroduced in a different light since working here: justice, freedom, and democracy. Lastly, I will touch on a personal note of working here, including both the joys and cautions of working in an international setting.

ABOUT MAZLUMDER

Mazlumder is a Muslim human right NGO that takes great pride in its role as one of Turkey’s leading civil society NGO’s. Offices are located in 27 different cities throughout Turkey, with headquarters based in the capital city Ankara. Mazlumder hopes to begin expanding internationally in the near future, with prospective sights set on Berlin, Washington DC and Cairo. Strict adherence to the NGO’s guiding principles are set in their motto:

“Kim olursa olsun zalime karşı, Kim olursa olsun mazlumdan yana”

Or,

“On behalf of the oppressed, whoever he or she may be; against the oppressor, whoever he or she may be.”

(Then again, “strict adherence” could be debated, and will be critically examined in Joel Arken’s paper on the Islamist human rights discourse which uses Mazlumder as a case study within the framework of a larger human rights narrative, as well as its own mission statement.)

1991, the year of its founding, historically proves itself to be a chaotic period for Turkish society and politics. The state towed a strict line of secularism and an ideal of what constituted Turkish identity, two major features of the republic’s founding that is still seen as division points in the country today. The concept of being an operating NGO in Turkey was still developing, making Mazlumder one of the trailblazers of the civil society movement. Today, Mazlumder is a coalition formed by different segments of society, represented in its boards members noted as of Sunni Muslims, Kurds, Nationalists, morally liberal Islamists, Iranians, and government officials (or otherwise described as “a microcosm of Turkish society” by one of its directors). It’s advocacy work ranges on behalf of Kurdish, Armenian, Rum, and Alevi populations; as well as women and headscarf related issues and refugee rights.

The organization is extremely well-connected and influential in Turkish society. An interview with Abdurrahman Babacan, Mazlumder’s Director of Foreign Affairs, shared that the organization was founded by 54 important, Islamist members of Turkish society in 1991 to protect the rights of Muslims in Turkish society, seen as the oppressed group at the time. Oddly enough, many of the founding members have since reached the ranks of the AKP government, including Prime Minister Erdoğan himself who was described as an “informal founder”. Other noted AKP links include the current Mazlumder chairman who previously served as an AKP parliamentarian, Turkey’s Minister of Culture, a former chairman of the Istanbul branch who now serves as a chief advisor, and Foreign Minister Ahmet Davotoğlu. Despite its links with high levels of AKP, Mazlumder claims that it does not accept government funding for its operations for reasons of operating with full independence and autonomy. Babacan has been repeatedly open in sharing that despite personal relationships between Mazlumder members and AKP government officials, it prefers to operate on these conditions so it may continue to openly criticize human rights infringements; this was made clear in the Taksim/Gezi Park protests when statements were made against the use of brutal police force much to the dismay of the AKP.

ALTERNATIVE DEFINITIONS FOR JUSTICE, FREEDOM, & DEMOCRACY

Working with this organization has introduced me to alternative conceptualizations of three major political and social norms: justice, freedom and democracy. In the West, these are easily assumed as universal values, but we must ask ourselves- whose value? Why do we assume a specific definition, without lending thought to how else it could be expanded, or added to, by different worldviews? By expanding our designations of what these ideas mean, is it possible to allow ourselves to redefine what they could mean on a larger scale? Could it begin healing the complete misunderstanding that the West has towards Islam?

As explained by Babacan, Mazlumder is chiefly guided by the concept of justice, whose full perspective is taken from the Koran. As repeatedly explained to us, the Koranic understanding of justice is not to be confused with equality, but rather is the inherent belief that encapsulates and informs a worldview of humanity where all beings are created by Allah. Therefore, humans should be sensitive to the problems of others and active against injustice. The reality of justice is such that recognition of an inherent responsibility to humankind will not always find favor with all.

Learning how Mazlumder organizes itself on a paradigm of justice, rather than freedoms or equality, and the fact that it is not interchangeable with these terms, is perhaps one of the most interesting aspects of working with this group. Will redefining and reconceptualizing equality come next? Perhaps this is so. Or maybe just a better understanding of how it too became a value of the West.

An alternative definition for the next concept, freedom, was introduced during an interview between Babacan and Luis Cabrera, a professor from University of Birmingham who specializes in Political Theory and International Studies. A discussion of the recent alcohol restrictions was underway, bringing up issues of freedom versus regulation. According to Babacan, the reaction to the limitations placed on alcohol purchases (which was one of the main grievances against AKP during the protests) was due mainly to Erdoğan’s tone and discourse which created the perception that the restriction was much bigger than it really was- what he prefers to call a regulation and NOT a restriction on the sale of a product. Mazlumder is in favor of the regulation, viewing it as a step towards restoring younger generations and creating opportunities for better lives for all Turkish society. It does not support the idea of endless freedoms, and rather sees the legitimization of things like alcohol and homosexuality as morally harmful. (Babacan did clarify that if a situation arose where gays were oppressed, injured, killed, etc., Mazlumder would protect their rights because although it may not seek to “legitimize their lifestyle”, it was still a human life.) From this conversation, human rights, freedom, and the moral view of human rights cannot be separated from each other.

In terms of democracy, rather than providing an alternative vision, Babacan posed some interesting points and questions for us to think about. He asked us, “What is the real meaning of democracy? How is it understood?” In Turkey, there wasn’t full support or belief in the Western version- a perspective that remains unclear. He continued, “Can we create an alternative type?” Can we look at the alternative types that exist in the West, Turkey, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, and Germany to see the differences that exist among them, as well as the different values and basis that each is founded on?

PERSONAL EXPERIENCE

Moving aside from its theoretical underpinnings and lessons, I will now shift towards the personal interactions of the past two months. At times, there were indeed some things that warranted relearning norms, most of which revolved around gender-based rules, like eating at a table with the females at lunch, separate from the men. That was fine. Maybe it should have jarred me more than it didn’t at all? By temporarily removing a feminist, equality pair of lenses, it’s a good, real, experience in how another part of the world is organized.

Other incidents and interactions have occurred on a smaller, more personal level. Be it in conducting three and a half hour interviews with our boss despite his fatigue, dry mouth, and hunger pains; and the way he lets us be involved in interviews and assignments. Or our older brother who keeps everything running as the behind the scenes guy. Another time it was an abrupt interruption to researching with, “Let’s dance!”, and a display of the best belly and folk dancing I’ve seen in Turkey yet. Maybe its in the openness to sharing a more conservative Muslim point of view. Or learning how to roll cigarettes on the balcony during an afternoon break.

Being here during Ramazan ,which began Tuesday July 9th and will close the remainder of our time here, has been an amazing experience. They aren’t kidding when they say Istanbul is an incredible city to experience Ramazan in. The month was kicked off by a huge Iftar picnic hosted by Mazlumder for its numerous Istanbul members. The event was a smash hit: Practicing Turkish with unassuming kids, a couple hundred people present, quality time with our coworkers, a delicious meal and breaking of the fast with comrades, followed by a night filled with copious amounts of çay with good company and a killer view of Istanbul from Fatih.

Other incidents have been a little jarring, although teaching. For starters, one resurfacing challenge comes in recognizing my own American-ness, and that being the first criteria that people view me through. I don’t want to write a laundry list of my “offenses” (wouldn’t you like to know!), because in the end I don’t think they are so important. They create an awareness of how I am received despite my best intentions to be engaged, interested, and respectful. In the end, the most we can hope for is that a narrative of “common humanity” prevails, just like Mazlumder says. At least, I hope so.

Journal Entry

Week 5

6.30.13 – 7.6.13

This week marks the official turn where we have less days remaining than those which we have already spent. There is always a tinge of sadness when you are working towards a final date in a place, only to be even more solidified by that plane ticket home. The first month was oddly marked by a wall I kept hitting; a perpetual and pervasive frustration that often clouded my vision of seeing Istanbul and her wonder. I kept trying to look past myself, but I wasn’t always successful. Thankfully, the succubus has vanished.

I’ve really wanted to avoid writing a journal entry laden with “epiphanies”. So instead, these are a couple of things I have noticed and wondered about this week as my eyes are seeing a little clearer, and a little brighter, than before. There is no shared theme among these things, just a collection of thoughts, lessons, and questions.

- Emerging from that funk made me appreciate this quote from I am Istanbul:

“There’s just something about this city. Something about its chaos, its refusal to compromise or fall in line, its willful rejection of its glorious past and headlong rush into its uncertain future. Its instinctive revolt against established rule. Yes, its nihilism and, above all else, its cocky self-assurance and ability to carry on, regardless of oppression and neglect! I love Istanbul just because it believes in itself! You could write a novel about it! I love the squawking seagulls and the drone of the ferryboats, the hushed silence inside the inner courtyards of the mosques, the profoundly mystical colors of Sufism…And I love the openness of the people. I love it! What more can I say?”

- You are hard pressed to find a cup of drip coffee in most places (No, this isn’t a rant on trying to find good coffee, that’s not my style). It is rather an observation that instead you are offered an abundance of Nescafe. Markets, menus, cafes- everywhere except chains like Kahve Dunyası and Starbucks, of course. “Coffee ne? Oh! Nescafe…”. It’s a good example of how an assumed good is replaced with a multinational corporation’s product line as a replacement. Nescafe has done a brilliant job of securing the market on that one. Bravo globalization.

- Most of the tensions in modern day Turkish society and politics can be traced back to the lines drawn when the Republic was founded in 1923. Those who were included in the legally drawn conception of what constitutes Turkish identity, along with what wasn’t, are the same divisions and rights that remain disputed today. I wonder, what is the difference between the emphases on the founding of the state in Turkey, with that in the US? Most questions that relate to Turkish sociological or political matters are approached within the context of how things were when the Turkish state was founded. I wonder, is this because 1923 is more recent than 1789, when the US put its founding constitution into place, so that in a sense it is still working these issues out but now in a modern context? At the root of this curiosity and surface comparison, I wonder what the pros and cons are to being so tethered, or detached, to the construction of the state that one is from.

- Similar to the above question, and maybe in a sense this answers it, I think it is important to understand that you can’t understand one’s identity without the history behind it. Nowadays in the West we focus copious amounts of energy on creating ourselves as autonomous agents, free from the drags of our family and the places that we come from. This individualized creation of one’s self removes the individual from being a part of a greater historical narrative. But you can’t fully understand, “now” without knowing what happened “then”. Sensational and cutting academic paraphrasing is insufficient if you want to grasp the entire picture. Trying to understand identity with a limited scope is a futile effort, reaping fruit that is unripe, bitter, and lacking the richness that could be bred otherwise. Collective and individual identity should be understood in terms of one’s sociological, political, religious, economic, and historical context (among others). Perhaps Western society aims to shed its historical allegiances and ties, but why? Is this one aspect of what cosmopolitanism is all about? What are the benefits of living free without ties, existing in a space where everything that you are is a testament of your own intention and creativity? What are the consequences and vulnerabilities of doing so? Lastly, what is the natural way?

- Istanbul has some of the most gorgeous bakeries; do they really sell all those cakes and goodies? What do they do with them if not, and how long do they stay good for? Hmmm.

- How much is the West’s preoccupation with “creeping conservatism & Islamization” really just a political fear manifested in the West? What is it trying to frame? Why? Would it really be so bad to have a more pluralized global political order? Instead of constantly reporting what should be feared, what if instead we approached the shift with what we could learn?

- There is an intentional skepticism of foreign actors in Turkey- at least for those of us working at Mazlumder. Two of the major events that have occurred in our few weeks here- namely the Gezi Park protests and the ousting of Morsi in Egypt- have been requested to be analyzed in a way that is critical of the West. For the Taksim human rights report that will be published shortly, we were asked to gather data from major foreign media agencies and analyze how the protests were portrayed. The emphasis was requested on Western media agencies: BBC, CNN, Wall Street Journal, NY Times, Economist, Washington Post, Guardian, Reuters, etc. Now with the recent events in Egypt, we are asked to examine the implications when the US labels such events as a “coup”, and why this would be a strategic move. Furthermore, there is a general desire to know why these types of moves matter, and perhaps even an underlying tone that seeks to change the surrounding discourse. I wonder, would this be such a bad thing?

- There is simultaneously never, and always, enough time for everything.

- In my next life, I hope I’m coming back as a seagull in Istanbul.

That’s all for this week. It sure does feel good to be out of wherever it was I had been the past couple weeks.

Journal Entry

Week 4

6.23.13 – 6.29.13

Strange that all of my journal entries so far have been about the protests. What can I say? They’re fascinating. While reading some articles this weekend, I made connections between the characterizations of modern day protest and the events that happened in Taksim. It is my gut instinct that we should be weary of the trends and guiding ideology that law enforcement is using in responding to peaceful protests. Tactics and official statements not only show an increasingly negative portrayal of protesters, the heavy police presence at specified peaceful protests is responsible for creating and reinforcing violent confrontations that occur, thus compromising one’s participation in the democratic processes. I will explain how this trend is manifesting itself in Turkey in conjunction with Kylie Bourne’s 2011 article, “Commanding and Controlling Protest Crowds”. [1]

Bourne begins with the assumption that peaceful protest and demonstration are a way in which citizens may actively engage in the processes of democracy. People are driven to protest as a means of political expression for a number of reasons: “To increase community awareness of an issue, to demonstrate the depth of public sentiment about an issue- when other forms of dissent have proved unsuccessful,…when they (citizens) feel that their elected representatives are not taking their views into account or when other means of public opinion are beyond their means.” [2] By their very nature, protests are disruptive; this disruption, however, should be understood in light of the day-to-day patterns of ordinary citizens that become temporarily inconvenienced while protestors take rightful advantage of utilizing a public space, as required, to hold their demonstration. As this journal entry will discuss, trends in crowd control suggest that governments and law enforcement agencies are portraying protests as disruptive due to an outdated and uninformed conception of gatherings, posing them as dangerous security threats that should be suppressed rather than as an expression of a functioning democracy. It is interesting to note that command and control strategies have replaced the previous, more civil model of “negotiated management”, as a response to public demonstration style since the 1960’s. In fact, command and control techniques resemble methods that date back to the late 1800’s/early twentieth century and have not been modified to adjust to today’s global reality. It is Bourne’s concern, and one with which I strongly agree, that popularization of “command and control” strategies since the 1990’s bears the majority of responsibility that compromises democracy’s right to protest. This becomes problematic because if peaceful protest is understood as a fundamental component of a healthy democracy, impediments to its exercise raise questions about the changing nature of the relationship between the citizen and the state, and furthermore, about the nature of democratic societies. [3]

For Bourne, the implementation of command and control strategies by law enforcement obstructs a citizen’s right to engage in peaceful protest within public space, including the mechanisms that protestors utilize as forms of political expression. Command and control is a method of policing crowds that became popularized in the late 1990’s to 2000’s via police training programs, yet is informed by a “mob sociology” view that precedes the shift that came from the protests of the 1970’s. This outdated conception of mob sociology views crowds as potentially riotous and violent and as an activity that is “distinct from civil life, rather than as constitutive of it”, therefore reinforcing the activity of protesting and being a protestor as grounds for suspicion that must be approached with zero tolerance for any signs of unruly behavior. [4]

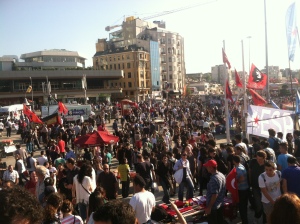

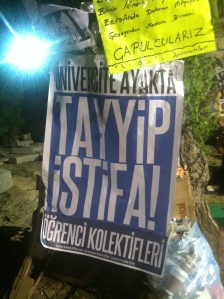

In Turkey, negative media portrayal of the protestors as disorderly and threatening caused a polarization within society that suddenly appeared to divide the country into pro-AKP camps and anti-government dissidents. These differences, which previously existed (albeit not at the same level of intentionality) had caused a rift that separated the protestors from Erdoğan’s supporters. The Prime Minister’s language towards the protestors further exacerbated these tensions by condescendingly writing them off as children, who if did not obey his deadlines, would be dealt with as terrorists. Oddly enough, while AKP’s tactics aimed to polarize civil society during the protests, the demonstrators were constantly hailed for their ability to organize around the issue despite their differences in race, ideology, religion, ethnicity, sex, age, and class.

Utilizing discourse of terrorism is one of command and control’s most effective and intentional features. In addition to alienating protestors as separate from civil society, it sets a precedent that they must be feared for their violent tendencies and irrational, unpredictable behavior. Even though it appears in fiction, Buket Uzuner had it right when she penned, “Here we are, at the beginning of this brave new millennium, and terrorism has already won; they’re trying to persuade us peace and democracy are luxuries we can’t afford.” [5]

By framing protest participants as terrorists, police justify arming themselves in full riot gear, adhering to zero tolerance policies towards the crowd, and overall dissuasion to keep people from attending at all. [6] The presence of things like aggressive machinery, police stationed in large numbers, dog squads, Special Force Units, officers clad in full riot gear, water cannons, and tank-like sonic weapons, all contribute to constructing a narrative that depicts protestors as a risk and separate component from everyday life. [7]

The tactics of command and control as presented by Bourne were witnessed and reported throughout the Taksim/Gezi Park demonstrations. In addition to negative portrayal of the protestors, public space became aggressively controlled and restricted by police force, despite the fact protest organizers specifically stated the demonstrations were peaceful. As mentioned in a previous journal entry, it was the brutal provocation of the police, to what Bourne would argue was driven by an ill-constructed threat of a crowd that turned the sit-in to save a park into a nationwide anti-government movement. Prior to this, the sit-in showed no violent tendencies by the protestors.

By the third day police had positioned themselves in such a way at the top steps of Taksim Square, on the adjacent south side of Gezi Park, as to grant themselves control to who could move freely between the two locations. Bourne states that limiting the number of physical entry points to a protest is meant to hinder communication between different sections of the crowd. [8] This “divide and conquer” technique makes it difficult for protest organizers to disseminate information within the crowd, obstructing any good intentions to keep the demonstration peaceful. Bourne writes that by materially limiting communication amongst the crowd, “things like changes to march routes cannot be disseminated and collective acts like chanting and the raising of fists or placards in unison cannot practically be undertaken.” [9]

Divide and conquer techniques can also mean fragmenting the crowd by pushing and cornering smaller groups into side streets, alleys, and neighborhoods. This becomes especially important when using tear gas and water cannons as means maintaining control and subduing threat. I remember the Saturday afternoon when protestors had been split between Beşiktaş and Taksim/Gezi. The group was on a ferry that afternoon crossing over from Kadiköy on the Asian side; from the water you could see the blows being shot from tanks aimed at a crowd of people inching by Inönü Stadium. Looking out onto the other boats in the water, I recall watching ferries carrying boatloads of young people to the protests cheering as they rode on their way to Taksim. Turns out, the ferries crossing the Bosphorus were packed with soccer fans from the Asian side of Istanbul that were stopped in their tracks by the ridiculously overzealous police force that awaited their arrival. The sit-in had turned into a two-front battle. The police line that received them upon docking closely resembled an expectant army anticipating invaders, not its own citizens. The nights that followed shared a similar story that saw protestors being divided and pushed out through the streets surrounding Taksim.

This regression of a militant approach to peaceful protest is problematic for a number of reasons. First and foremost, if you share my fear (or frustrations, observations, nightmares) of an impending worldwide police state, this won’t ease any nerves. By compromising the process of peaceful protesting, citizens are deprived and further removed from a critical component of democratic participation and thus reduced to be recognized as villains who must be tamed. Second, by criminalizing demonstration, merely being present at a protest poses the liability of being labeled a threat to the state. We should critically examine what this implies when exercising one’s democratic right to express disappointment in a government immediately becomes entrance on a watch list. Lastly, this zero-tolerance approach towards the right to protest serves as a justification that will only further polarize civil society from those in authority. Moreover, it denies a history that showed success in cooperation and diplomacy between government, law enforcement, and populace.

As it stands, worldwide trends that show the withering away of dialogue and conciliatory action between state and citizen are alarming and unsettling. As the might of the powerful has advanced, so must the methods of protest. A July 1st article titled “You Say You Want a Revolution?” in Foreign Policy acknowledges the power of protest, but also its inability to produce real change in the wake of the initial gathering. While pointing out a shortcoming, David Rothkopf presents readers with an opportunity: “The revolutionaries (of present) were better at organizing protests than they were at institutionalizing their movements or creating, cultivating, and empowering leaders who could master existing institutions.” [10] In an era where horizontal leadership is becoming the new norm of protest organization and social media is the great mobilizer, we must critically examine what else will comprise civilian mobilization as we look towards the next phase. Rothkopf writes,

“It is great that new technologies enable crowds to gather quickly, communicate among themselves, learn new slogans, and be briefed on the latest developments. They can help translate feelings into nationwide actions with unprecedented speed. But if the elites have the money, control the military, control the police, control the mechanisms of political expression, if they can use the means of the state to suppress upheaval or if they can exploit revolutions to advance their own agendas versus those of other elites, they become hard to dislodge — especially for movements without real leaders, clear agendas, strong political organizations, or effective plans for enshrining their values were they ever to gain power.

…

That underscores a point long understood by many students of power: The greatest force to be overcome in governments and societies everywhere is inertia. Demonstrations are easy. Lasting change is hard. Those who hope for it in the Arab world and elsewhere must focus more on training oppositions in the long game of getting and consolidating power and less on how today’s chants are playing on CNN or in the Twitterverse.” [11]

NOTES:

[1] Source: Bourne, Kylie. “Commanding and Controlling Protest Crowds.” Critical Horizons. 12.2 (2011): 189-210.

[2] Bourne, 190

[3] Bourne, 191

[4] Bourne, 197

[5] Source: Uzuner, Buket. I am Istanbul. 2013, Dalkey Archive Press.

[6] Bourne, 203

[7] Bourne, 205

[8] Bourne, 201

[9] Bourne, 201

[10] Source: Rothkopf, David. “You Say You Want a Revolution?” Foreign Policy. 6.1.2013. http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2013/07/01/you_say_you_want_a_revolution_street_protests?page=0,0

[11] Ibid.

Journal Entry

Week 3

6.16.13 – 6.22.13

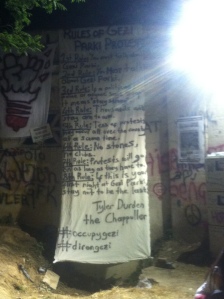

“Hope for a day when people do not fear the government because the government fears the people!”

“When injustice becomes law, resistance becomes duty.”

Perhaps now is the time to put a couple things into focus. And by a couple of things, I mean this innate desire to understand resistance and the ways that I see it manifesting itself around the world, especially in the past couple of years since I started taking notice. It continually draws my attention to its core. Perhaps even all of us in this program. Let me begin by explaining how this attraction and interest brought me to Istanbul in the first place.

I am a strong believer in the cycles of life; the circulation, the power of regeneration and restoration, the round nature that continually defies angular, formulaic knowledge. This last week I had the experience of life, for roughly the past year and a half, come full circle. I don’t believe it to be the final stage of this circle, but rather, a marking of the beginning. Allow me to explain.

In late October, 2011, I was living in Southern California watching the events of Occupy Wall Street transpire in Lower Manhattan’s Zuccotti Park, a country away from where I was. Constantly in tears while watching videos and reading pieces written by Occupiers, I became entranced by the message that was coming out of the gathering. In one of my favorite articles, “If We Get Occupy Right, We Get Everything Right”, Ian MacKenzie writes,

At its heart, Occupy is not a protest. It’s about creating space. It’s about modeling a new way of being, that requires a fair amount of “unlearning” the way society and human nature has been taught. It’s asking the question: why? Why are things the way they are? Is it, in fact, human nature to be greedy, violent, and cruel? Or is it possible that these are symptoms of a systemic order? Occupy Wall St is also about rejecting a system that has, at its core, drifted violently out of balance. It has become life destroying – and no amount of material wealth will stave off the underlying sadness of that realization. [1]

I decided that if something like this was going to happen in my country, I had to see it. So, I booked a flight to New York to witness the demonstration. I suppose this is why it’s called a “movement”. It starts with a single act of getting up from where you are. From there, anything can happen.

After spending a few days in the city, wrapping up what I set out to do (observe and see Occupy with my own eyes, to just be there), I woke up to head to the airport to return home. Except this morning, Wednesday, November 16th, 2011, was unlike the others. Upon turning on the news, images blasted nearly every channel with footage showing a police raid on Zuccotti Park from the previous night. [2] I was paralyzed; going home seemed the most unimaginative option of everything that went through my mind. Still, I boarded a plane back to California, certain that I would be back in the city within a year. Immediately upon returning home to California I applied to The New School; my application was finished in record timing. It would be less than nine months before I was back- ready to follow whatever it was that this movement, in this city had sparked in me. (Okay, so typical New York. Amiright?)

Fast forward to almost a year later since the time I stepped in New York to go back to school, a decision that entailed a complete field change after nearly five years of being outside academia in a completely irrelevant field for what I was now pursuing. I know many find themselves in this same, rather precarious situation. All I can say is that it involves quite a learning curve, one that offers humility at every point along its path. I decided on The New School because of its reputation as a force within progressive academia. I believed this to be the place where I would be trained to ask the questions that I knew were in me. From that trip in November, The New School and Occupy Wall Street became an inseparable fascination- their lure was completely intertwined as far as I could tell.

Having completed my first year in the International Affairs MA program, I am now in Istanbul, where these reflections come from and new opportunities for research abound. It is here that my circle became full, and alignment, once again, shifts into place. Since arriving, the news has been filled with the unrest in Turkey and Brazil. I began to contemplate if the demands and grievances were aimed towards similar structures, and whether or not they resembled those of Occupy Wall Street. These thoughts inspired a mid-game strategy change (aka- research topic shift), and I was reminded of the original catalyst that made it possible for me to be in Turkey in the first place. My new research topic may not even incorporate OWS, but I think it is important to keep in mind that what we are witnessing is a response from civil society against the bleak conditions created for the majority of the world by those in power. I believe that this is a far deviation from the natural order of the world.

So, a full circle completes itself when I recall that what started this path was a flight out of NY on the day when a park’s occupation was turned upside down, only to land in Turkey on the day a park’s occupation was born.

In terms of my new research topic, I am curious about the similarities and differences between the protests that comprise this new wave of resistance. I know extensive research has been done by those with the same skepticism that I have, especially in regards to the anti-globalization protests at G8 and other summits during the 1990’s. Naomi Klein, a well-known Canadian author and social activist who is best known for her criticisms of politics and corporate globalization, gave a speech at Zuccotti Park on November 6, 2011, marking an important shift from the “anti-globalization” protests she had previously participated in. Klein spoke of how the Seattle 1999 WTO protests were different because their targets were summits, whose very nature is transient. She writes that, “We’d appear, grab world headlines, then disappear.” For Klein, OWS represented an important evolution from this previous method of confronting corporate power because it,

… has chosen a fixed target. And you have put no end date on your presence here. This is wise. Only when you stay put can you grow roots. This is crucial. It is a fact of the information age that too many movements spring up like beautiful flowers but quickly die off. It’s because they don’t have roots. And they don’t have long term plans for how they are going to sustain themselves. So when storms come, they get washed away.” [3]

While Occupy’s target has been scrutinized for losing its aim on a “fixed target” that Klein so vehemently praised, a lot other aspects that she mentioned remain true. Occupy remains a network of activists, despite a retraction from the political limelight. One could argue that it seeks to gain legitimacy and authority for stating solidarity with other struggles around the globe that share similar frustrations. [4] Others debate whether or not it was effective in the first place- what did it change? This is a valid question; however, let us not forget that this idea of “waking up” may still be in beta. In the same speech above, Klein called the movement “the most important thing in the world”; perhaps what she said is true as we continue to witness similar movements sweep the national conscious of countries around the globe [5]. Those movements too, in turn, become a part of the most important thing in the world. The phenomenon of a global awakening is fascinating. It captures the core of imagination.

I hope to add to this body of research by seeing whether or not these types of movements are able to take root. And if not, what should be considered in terms of strategy. And whether or not we actually stand a chance against a polarizing, inanimate, homogenous corporate world order that forces humanity closer together. Every day our lives become a little more like science fiction (maybe I’ll touch on this next time!)- and these demonstrations are just another example of man versus machine. Corporate power compromises democratic power. If occupying space is the modern mechanism used to maintain a dialogue that keeps this in focus, we must begin focusing on the next effective phase that guarantees the just processes of democracy.

Ian MacKenzie captures this sentiment perfectly. After all, this is reflection on the past for what propels me in the present and in the future.

“We have realized that we suffer from a severe lack of imagination, and are crying out for a potent new vision of the future. I believe I have experienced a taste of this new vision, what Charles Eisenstein calls “the more beautiful world our hearts tell us is possible.” And it is because of this that I can demand nothing less.

Allow me to share a potential vision:

What if the Occupy Movement truly is the latest manifestation of the paradigm shift that is rippling around the planet, what Paul Hawken calls “the blessed unrest”? What if this shift is characterized by a new recognition of the self, one that no longer betrays ourselves as separate beings in an indifferent universe, but realizes we are conditional upon all the relationships we share?

I am because you are.

What if we experimented and perfected this alternative model of being, and deployed it along the vast global information network already encircling the globe? What if this model allowed us to grasp the array of crises plaguing our lives and the planet as actually interconnected – and to truly understand one was to understand and change them all?”

I wish the best for the seeds of the past and the present as they begin to sprout. I thank the initial wave of 2011 that now makes me cheer when the fight for democracy continues on.

NOTES:

[2] For a beige description of the events, see Al Baker & Joseph Goldstein’s NY Times article “After an Earlier Misstep, a Minutely Planned Raid”, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/16/nyregion/police-clear-zuccotti-park-with-show-of-force-bright-lights-and-loudspeakers.html. For footage of the raid released almost a year later by Anonymous, see http://www.salon.com/2012/09/24/nypd_footage_of_zuccotti_park_raid_leaked/ instead.

[3] To see this speech in its entirety, see: http://www.bresserpereira.org.br/terceiros/2011/11.10.Naomi-Klein-TheMostImportant.pdf. Source: Klein, Naomi. “Occupy Wall Street: The Most Important Thing in the World Now.” The Nation. October 6, 2011.

[4] For example, today’s top headlines on Occupy Wall Street’s website include, “Mobilize for Bangladeshi Workers: Mass Funeral Procession to SoHo Retailers”, “Saturday, Zuccotti: Solidarity Action for Brazil, Turkey, and Greece”, and this art:

For more, visit: http://occupywallst.org/

[5] Klein, The Nation.

Journal Entry

Week 2

6.9.13 – 6.15.13

[ Author’s Note: Much of the first half was written between 6.8 – 6.16, prior to the violent second face-off with police. The park now remains occupied by police forces. Over 5,000 people have been injured in Turkey’s protests, and many have been arrested from their homes. This writing does not reflect the protests since these events have taken place. ]

I am just as guilty as everyone else. I’ll begin with stating that.

What is happening in Turkey is historic. One word that is shared among those of us experiencing Turkey’s fight against life-numbing complacency and unsolicited compliance is that the entire course of events is surreal. [1] Furthermore, it IS real. So what really gets me, is that as we become witness to a grand battle of democracy and authoritarianism, everything is a photo op. Everyone is busy posing, or waiting to snap, the latest and greatest shot. So you better make sure it’s good.

I’ve discussed this with my colleagues, and the consensus appears to be it is just the new nature of the revolutionary beast. Times have changed. In terms of broadcasting events, “the revolution will not be televised” has evolved to “the revolution will be tweeted”.[2]

I am not here to belittle social media and its powerful role in mobilizing the populace throughout the region, especially considering the world became witness to its role during the Arab Spring that began in 2010. Far from it. For some, the social media outlet is empowering and holds great emancipatory power. Organizations like Cyber Dissidents understand its role, and create a platform that “highlights the writings and activities of dissident bloggers in order to strengthen their voice and defend their freedom of expression.” [3] By connecting citizens in Syria, Sudan, Canada, Russia, Egypt, Iran, Israel, America and Jordan, Cyber Dissidents utilizes the internet to organize and connect activist networks that share its founding principles of freedom and democracy. It is through social media networks that this NGO is able to make these connections and demands on behalf of activists in the first place.

So yes, voices must be heard. One thing we were repeatedly asked of during the first days of the protests was to inform the foreign media of what is going on. It took the world days to respond as the country was lit ablaze. It should be an outrage that it took copious amounts of pictures and footage of the events in Taksim Square to convince the world that what was happening was newsworthy and deserving of the world’s attention. The sad thing is that this can be said for most crises. People lament for the media to respond, but it takes days. And when it does, it often is quite short-sighted. So if the media isn’t doing its job, and when it does it has to post the most sensationalist form of the conflict in order to keep the attention span of an audience, everything becomes highly subjective to a person’s interest. This should be a huge problem, because if the latest number of 93,000 people dead in Syria doesn’t strike a chord, it makes me wonder what we are all doing. [4] Have we become conditioned to be numbed to disaster? Delays in mainstream reporting and its blatant subjectivity grants legitimacy to social media in that it hands power back to the people.

One thing that I noticed from international coverage of the protests during this rather peaceful week in Taksim and Gezi is that it is “news” when there is no violence. [5] The problem with this, however, is that since the initial retreat of the police after the first weekend, the square and the park have embraced a contagiously positive energy. The reality of the situation this week then, is that in the absence of a police presence, it is news when it is violent in Taksim, not the other way around.

We must ask, why the reluctance to report that thousands of people are gathering for days in PEACE? To occupy a space until their democratic rights are restored and acceptably recognized? In my opinion, this begs larger questions about the nature of order and the role of police and fear. This week, the absence of police and a brutally imposed idea of order has seen groups that have historically been pitted against each other in Turkey, now cooperating and coexisting together. The list is comprehensive, transcending traditional divisions in terms of political, ideological, religious, class, gender, race, soccer allegiance, age, etc.[6] I wonder then, what is the natural state of society? When a police apparatus is removed, are our natural tendencies towards a cooperative collectivism, or fear and distrust of the other? Furthermore, how strong and how pervasive must the baseline grievance be that it binds these different sectors of society together in a united front?

Media portrayal of the Taksim events raises some interesting points. For example, one Turkish professor who had not been to the protests asked what they were like. When we shared that the environment was quite joyous and had a festival-like atmosphere the past week and a half that the police were absent, he was baffled. He couldn’t believe people could be jump-roping and celebrating there, when the news was filled with images that made it look like a perpetual battlefield. This is true; most of the pictures make it look like the events are taking place in a war-torn desert nation, not the center of a European city.

It makes me think that these images are reinforcing an image of Turkey that the West continues to force on the country, cropping images that leave out the entire picture. This includes the elderly that sit on the sidelines, present at the Taksim yet watching the youth construct the barricades. The couples who have come to Gezi Park after their wedding to show their solidarity. The lawyers who led a march down Istiklal Avenue. The dancing, the peace lanterns, the food vendors, and the martyrs. EU delegates were in Istanbul when the state of the area reflected this. So why now does this threaten Turkey’s EU prospects (if there were any remaining). [7] The news depicted a rather grim picture of how this week’s events actually transpired, and they had the chance to see it with their own eyes. Perhaps they were just waiting for a good excuse.

If anyone takes interest in 2012 theory, maybe what we are seeing is the breaking of what Daniel Pinchbeck calls the “crisis of consciousness”, where humanity enters into a new period of time that the Mayans believed would mark a shift into the next age of man. [8] This next age is believed to be an awakening that would confront our ecological crisis and the structures that deplete it, replacing it with a universal conviction of stewardship and social responsibility.

Perhaps that is one way to characterize the demands of the Taksim protests: a vision that life can be better than this. That there is still dignity in being alive, despite the power that those in authority become accustomed to. One sign from #occupygezinyc shows a sign from protesters in front of the Turkish Consulate in Manhattan that states, “A tree died, a nation woke up.”

At first I was annoyed. The Turkish people are intelligent, generous, hospitable, timeless, and proud of who they are. They have to be, it was part of their plan to resist the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire after WWI. At first I thought it was ridiculous Americans saying that the people “woke up” to realize the value of democracy, without realizing they had been “enjoying” it for years. But then I thought about it in terms of resisting the man, and I remember that the experience of an awakening is beautiful. Hell, everyone should try it! Imagine that world.

So not only is the story given to the protests by the media a determinant on how it’s perceived by the world, but we must consider the actors themselves. I deeply admire the protesters in Gezi and Taksim; that should go without saying. What I do find funny though, is the photo ops that these situations create. Because whether it’s the young man holding a pose to wave an Ataturk flag on top of a barricade with the most badass handkerchief on while the photo journalist snaps away in front, or the old man reading during the Standing Man demonstrations that attracts throngs of photographers by raising a peace sign, I’ve seen countless people ensure they are posing- while simultaneously participating- in the revolution. In the end, I suppose the only thing that matters is letting the word out to the world. And taking timeless shots in the process.

I’ll close with this thought. Near my home there is a Quaker church that weekly posts inspirational quotes on its sidewalk bulletin. I remember one, from when I was 14 or 15 that went something along the lines of the things that bother us most about other people, are the very things we embody. So, we can’t smugly tell someone they have something in their teeth, when we ourselves have pen written across the length of our cheek. That being said, while I poke at the authenticity of current events, and the trend of posing for them, I unfortunately have to go so I can post my newest pictures to Facebook before today’s news is obsolete and someone posts cooler photos than mine.

Week 1

6.1.13 – 6.8.13

It’s been over a week since arriving in Istanbul. Considering the events of this first week, it’s unclear how the rest of the summer will unpack the circumstances that awaited us upon landing. The day we arrived marked the tipping of a bucket full of Turkish discontent, spilling entirely on Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and the Justice and Development Party’s (AKP) politics.

The political climate we currently wade through started as a peaceful sit-in to save Gezi Park, the public green space adjacent to Istanbul’s transit and social center Taksim Square, from a government-backed plan that will allow private contractors to demolish the space and erect a shopping mall and apartments in its place. This project entails a horrific modification to the existing traffic situation that plagues Istanbul, allusions to the construction of a mosque, and demolition of the Ataturk Cultural Center. The protest is no longer focusing solely on this dimension; it has turned into a massive uprising against the gradual hypocrisy of the AKP’s leadership and its policies that encroach on the lifestyles of this secular constructed society. The fortuitous timing of these events should not be lost on us, nor should they be taken for granted. If we consider ourselves as eager observers and students of world events, we have become unintentionally immersed in a situation of political dreams. [1]

As many will likely be writing about this topic our first week, it is justified by doing so. Turkey, as always, is surrounded by tensions. Is this just another domino in the worldwide trend of youth discontent? Have youth always been so? The grievances appear to be the same in countries around the world that succumb to the growing sense of disappointment. Former Turkish Minister of Economic Affairs, Kemal Derviş, writes, “The events that started in Taksim Square are specific to Turkey, but they mirror aspirations that are universal.” [2] In the U.S., grievances, although lacking Turkey’s poignancy, targeted an economic system that failed to deliver an equitable and sustainable future. In countries throughout the Arab World, especially in Tunisia and Egypt, thousands of citizens poured into the streets to fight against the despotic regimes that perpetuated their poverty. While successfully overthrowing their authoritarian governments, the future of both countries remains to be determined as transitional governments navigate through troubled waters and empowered citizens. And there are those like Syria, whose attempts to oust brutal dictator Bashar al-Assad, have spiraled into a civil war that continues over two years later.

As these examples continue to rise around the globe, what is the source of this time period’s angst? Is it us, or is it those who lead and the taste of power that lingers on their breath? This sense pervades borders, colors and countries; yet the base line argument remains similar. Derviş states it is, “The renewed patriotism seen in many places – a response to the unfairness and dislocation that globalization can generate – must be reconciled with human solidarity, respect for diversity, and the ability to work across national borders.” [3]

I do want to mention that the Taksim redevelopment agenda Prime Minister Erdoğan is charged with during #occupygezi, is actually part of a long-standing plan that dates back to the mid-nineties when the Welfare Party, an AKP ancestor, was in power. Perhaps because I do not speak Turkish, I cannot confirm if this is blasted in the media and on the signs that wallpaper Taksim Square and Gezi Park.

According to Jenny White, former Welfare Party founder Necmettin Erbakan had a vision for the role of the nation’s first Islamist party. According to White, Erbakan,

“…planned to pursue a brotherhood of Muslims around the world, replacing Turkey’s ties with and reliance on the West. After the 1994 elections, several attacks were reported on women in Western dress in Istanbul, and attempts were made to separate women from men on public transport. Some Welfare mayors had statues of nudes removed from parks and tried to close or restrict restaurants and nightclubs that served alcohol. In a direct affront to the institutional legacy of Kemalist secularism, party zealots proposed building an enormous mosque in Istanbul’s Taksim Square beside the modernist Ataturk Cultural Center, which hosted Western-style opera, ballet, and symphonies.” [4]

The Welfare Party was eventually replaced by the Virtue Party (VP), also master-minded by Erbakan, who this time was removed from the limelight. It was, “Welfare’s experience of persecution that pushed the Virtue Party’s platform and rhetoric in the direction of democracy and human right, political freedom and pluralism. While Welfare was a political party defined by its relation to Islam, Virtue, represented itself as a Muslim party defined by its relation to politics.” [5] It should come as no coincidence that Erdoğan was the incumbent Welfare Party mayor of Istanbul in 1995, during the time the above party agenda was pursued. He would continue to rise in leadership as the Welfare Party evolved into the Virtue Party, and eventually become the founder of the Justice and Development Party in 2001. Understanding the trail of Erdoğan’s rise to power with a nebulous political alliance and the Taksim agenda that follows close behind almost twenty years later, makes today’s protests sound eerily familiar.

It raises the question: what are the forces driving AKP? Studying the intricacies and complexities of Turkish politics instills that one should always be skeptical of the hidden actors, manipulators, and motivations. While being elected under the guise of a conservative democracy, the creeping measures the AKP passes that are gradually conservative in nature and lacking of democratic consultation begs to ask about the strategic plan of the party and the vision it has for Turkey. This continues to be the basis platform of the protesters in Taksim Square, and will continue to be criticized despite the popularity the party has enjoyed up till recent events.

My final thought is this: are we witnessing an attempt at a political project that is just another case of a leader taking care of unfinished business from the past? [6] Can there be reconciliation between these pet projects and the interests that guard them, with the greater desires of society and the processes of democracy? Around the world citizens are lit aflame. As we reach for greater democratization and justice, the grasps of those in power become ever firmer and swift to punish. Clearly, this is no longer merely about saving a park in Turkey. But perhaps by uncovering the historical dimensions of the initial issue that tipped the bucket, we can understand the effect the spill will have on Prime Minister Erdoğan and future of democracy in Turkey.

Media

NOTES:

[1] That is of course, unless you’re wealthy enough, in which case, you could have tickets on demand to the latest breaking national crisis of the world’s hotspots.

[2] Derviş, Kemal. “Taksim and the Left.” Project Syndicate, June 2013.

[3] Ibid.

[4] White, Jenny. Muslim Nationalism and the New Turks. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013.

[5] Ibid.

[6] George W. Bush’s invasion of Iraq is regarded by many as finishing daddy’s business from his term in office for a number of personal and political reasons. For a summary of these skepticisms, see Toby Harnden’s 3.18.03 article in The Telegraph, “Unfinished business for the Bush family – and, yes, it’s personal”.